An aerial video clip is shown of a nation’s capital: streets full of chanting protesters and rioters, buildings with fire in a window here and there, police pressing crowds back in a jagged line of non-violent violence; a voice-over begins to explain to us what we see and briefly speculate on what may result. Within thirty seconds, the screen has shifted back to an impersonally friendly anchorperson and then, after a snippet of a motif from the ‘theme song’ of the news, we’re into fifteen seconds of a toothpaste commercial. When the ‘news’ returns, it will doubtless be after several more ads have run and we may be hearing about microchip brain implants for the visually impaired, celebrity gossip for the intellectually deprived, an extraordinarily shocking sports injury, the dietary habits of East Asian forest-dwelling mammals, an unsolved gruesome murder case or an upcoming national election. Each of these will be ‘covered’ in a few minutes or less, interspersed with rapid-fire advertisements, and after viewing for an hour or two we are able to consider ourselves ‘informed’ and ‘up-to-date’.

Has the absurdity of this kind of communication, this kind of ‘informing’, ever struck you in a moment of quiet reflection? If so, you would probably like to read the work I am reviewing today. If not, you need this book desperately and ought to reserve your copy from the local library before you eat your next meal.

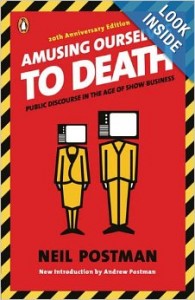

The first chapter of Neil Postman’s best-known book summarizes his concerns in the following words:

Our politics, religion, news, athletics, education, and commerce have been transformed into congenial adjuncts of showbusiness, largely without protest or even much popular notice. The result is that we are a people on the verge of amusing ourselves to death.

Amusing Ourselves to Death is an easily followed argument, originally published in 1985, in defense of the cultural assessment quoted above. What Postman observed was the gradual metamorphosis of what he calls public discourse from the late nineteenth century through the late twentieth – a shift, ultimately, in primary communicative technology that has changed the way we understand both communication and truth. The foundation of his assertion is the idea that technologies are never neutral; that each comes with a built-in agenda or predisposition to frame reality in a particular way. The shape of that agenda gradually affects the shape of our understanding of the world through the power of metaphor. Thus, for example, the prevalence of machines in our daily life since the industrial revolution has gradually altered the way we think of the earth and galaxies, ecosystems in the created order, and even our own minds and bodies: we have a tendency to view all of these things mechanistically, or from an amateur engineering point of view.

Postman says it succinctly: ‘How we are obliged to conduct [human] conversations will have the strongest possible emphasis on what ideas we can conveniently express’ (emphasis mine); and in another place, ‘The concept of truth is intimately linked to the biases of forms of expression.’

To present his case, he takes us on a brief tour of American media history. A major point he must establish is that media culture has seismically shifted. America was once a literary nation, ‘dominated by the printed word,’ and the dominance of this form of public discourse shaped private and public life. The shining example of the difference between the literary culture and our own is Postman’s account of an early debate between Lincoln and Douglas in rural Indiana, where the town turned out to listen to seven hours (with a dinner break) of closely reasoned rhetoric. He gives other illustrations that serve, more than anything, to show us how foreign that culture seems to us today. My other favorite is his reference to the stark contrast between the theological arguments of Jonathan Edwards and the recent writings and appearances of prominent Christian leaders (when he wrote in the mid-Eighties) like Jerry Falwell, Oral Roberts and Billy Graham.

After successfully highlighting the transition into the new paradigm, noting that the telegraph was the beginning of the end because it was the first device enabling the disconnection of information from context – changing the definition of information and turning it into a commodity – Postman explains how television (and by extension, much image-based media) has facilitated the transformation of all our public life into entertainment. News, religion, politics, and education are each examined in turn, revealing a good deal about the way we now see (or miss) almost everything.

What is the cumulative effect of these changes? Take the news as an example. Ever since the telegraph, irrelevance has become the measuring stick for relevance, and knowing ‘things’, and lots of them, has has become vastly more important than knowing about anything. “How often does it occur that information provided you on morning radio or television, or in the morning newspaper, causes you to alter your plans for the day, or to take some action you would otherwise not have taken, or provided insight into some problem you are required to solve?” ‘News’ has become anything but. “We are presented not only with fragmented news but news without context, without consequences, without value, and therefore without essential seriousness; that is to say, news as pure entertainment. . . . It is simply not possible to convey a sense of seriousness about any event if its implications are exhausted in less than one minute’s time.”

Consider the (im)possibility of televised religion: “There is no way to consecrate the space in which a television show is experienced. . . . I think it both fair and obvious to say that on television, God is a vague and subordinate character.” As a Christian myself, I find his opinion of the effect of televising Christianity astute: “I believe I am not mistaken in saying that Christianity is a demanding and serious religion. When it is delivered as easy and amusing, it is another kind of religion altogether.”

How can political ends be accomplished across the airwaves and through screen time? Commercials have become the paradigm for political presentation on television, which means that the pragmatic campaigner will observe that “short and simple messages are preferable to long and complex ones; that drama is to be preferred over exposition; [and] that being sold solutions is better than being confronted with questions about problems.” It is difficult in this environment to know how to proceed, or even to assess where we are, because “with media whose structure is biased toward furnishing images and fragments, we are deprived of access to an historical perspective.”

And in perhaps the most important arena of human responsibility, teaching the next generation, have we erred in looking toward technological saviors? “We now know that Sesame Street encourages children to love school only if school is like Sesame Street. . . . The most important thing that one learns is always something about how one learns.”

Maybe that last point is among the most critical to remember. Each of us is learning all the time, and as Postman incisively comments, “Television is a curriculum.” We are often concerned about the content of our media, but we are reluctant to pay attention to the ways that the shape of our experience is shaping us. As long as we stay in this society, there is no turning back the dial; America is, after all, “engaged in the world’s most ambitious experiment to accommodate itself to the technological distractions made possible by the electric plug. . . Who is prepared to take arms against a sea of amusements?” It may be that we are not ready to take arms in that battle, and it may not be the most important battle we face. If it is not front and center among the issues of our day, my sense is that it is nevertheless present and that it touches most aspects of our lives.

Have we stopped thinking deeply? Are we constantly amused, or expecting to be so, and always searching for the next bit of fun? And if so, do we know why, and is there a possibility for change on a large scale?

I hope that Postman’s book can still serve as warning, wake-up call, and as a goad to our oft-lazy souls. Let’s take stock of our lives and our time; let’s consider what is making us who we are, and what choices lay open to us for a more promising future together.